North America, Part 3

Before the late 17th century, indigenous Indians were the primary population, but they formed no national theater groups. By the 18th century, former Europeans had become the majority in North America, but unlike Europe, North America could not boast of any internationally or even nationally famous entertainers. Between 1642 and the 1790s, sporadic theater bans in France and other continental European countries, as well as in England and North America, impeded the development of drama. These prohibitions were imposed by the Catholics and Puritans, British politicians, and even the Continental Congress, each fearful of losing power over its targeted groups.

In 1778, after a difficult winter, George Washington ordered his remaining troops to perform the play Cato at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, despite the Continental Congress’s ban. Invited citizens packed the house.

For a period after the Revolutionary War, America’s circus performers, unlike its musicians and actors, could make their living, or at least earn scant lodging and enough food to remain healthy. In Europe during the late 18th century, circuses were ubiquitous, and some of them traveled to North America. In 1792, Englishman John Bill Ricketts arrived in Philadelphia to develop America’s first full-fledged circus. It was a hit: even George Washington enjoyed a performance, and five years later, in Montreal, Ricketts established the first Canadian circus, which was also heartily received.

North America’s female entertainers were considered vulgar—as lowly as prostitutes, or at best slightly better. For a member of the fair sex to support herself in entertainment, she had to be unique or develop a spellbinding act. The women who became acclaimed circus performers were either freaks of nature, or highly skilled at an interesting specialty, or a combination of the two.

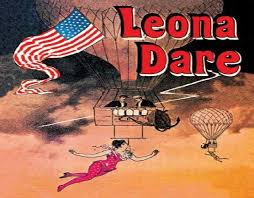

In 1854, Leona Dare was born. The future American circus daredevil’s original name was Susan Adeline Stuart, but she changed it to Leona Dare at age sixteen when she debuted as a performer and married her mentor and fellow acrobat Thomas Dare, of the Brothers Dare. By 1872, Leona’s act was enhanced, thanks to the amazing strength of her jaw and a supplemental iron jaw invented by the Brothers Dare. As her shapely body, in a glittering skimpy costume, dangled beneath a hot air balloon, Leona gripped her teeth over the iron apparatus, which secured the waistband of a male acrobat, and maintained her bite as the balloon rose hundreds, then thousands, of feet.

Leona traveled to Europe and became internationally famed after her performance at the Folies Bergère in Paris. Afterward, her life became more complicated: 1) In 1875, she and her husband separated (it’s debatable who left whom). By 1880 she was ostensibly married again, to a well-off gentleman, but when it became public that Leona was still legally married to Thomas Dare, she got a divorce in absentia and two days later remarried her wealthy man; 2) in 1884, Leona accidentally dropped her partner, who died of his injuries; and 3) in 1890, a year after she’d reached her height, figuratively and literally, of 5,000 feet above London’s Crystal Palace, she repeated the act in Paris. On the ascent, a blast of unexpected wind caused the balloon to drift away, whereupon Leona deliberately let go of her trapeze, fell, and broke her leg.

In 1922, Leona Dare died at age sixty-seven after approximately thirty years of retirement. Her original costume and mouthpiece are displayed in Spokane, Washington, at The Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture. During her halcyon days, Leona had been billed as The Comet of 1873, The Pride of Madrid, and Queen of the Antilles.