North America, Part 2

Several years later, Lillian (the future Native American movie star) met the charismatic James Young Johnson, who thought he wasn’t Native American but masqueraded as a Winnebago, Lillian’s heritage. Though James was officially classified as a mulatto (a racial category then used to refer to people of mixed African and European ancestry, its use now considered dated and offensive), he was truly 50 percent Nanticoke Indian. He was unaware of that because his father had died before James’s first birthday—though his mother was likely mulatta or white.

James joined the navy during the Spanish-American War, and resented the disrespect he received due to his alleged 50 percent Black African blood. After his discharge he told people that he was an American Indian. This helped propel his career in entertainment because American Indians garnered respect during the early 20th century, and there was a demand for authentic-looking Indians who were skilled horsemen. James had performed as a cowboy with the Barnum and Bailey Circus and as a son of the Wild West in the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West Show.

In 1906, twenty-two-year-old Lillian married thirty-year-old James, after which they performed together in New York and Philadelphia. The Ghost Dance, by then accepted, was part of their repertoire. By 1908, Lillian had landed a bit part in her first silent film, The White Squaw. By 1909, husband James had begun acting in several one-reel westerns. That same year, after Lillian’s second film, The Falling Arrow, the pair worked as technical advisers and extras for another two films. Moving Picture World labeled them “perfect types of their race.”

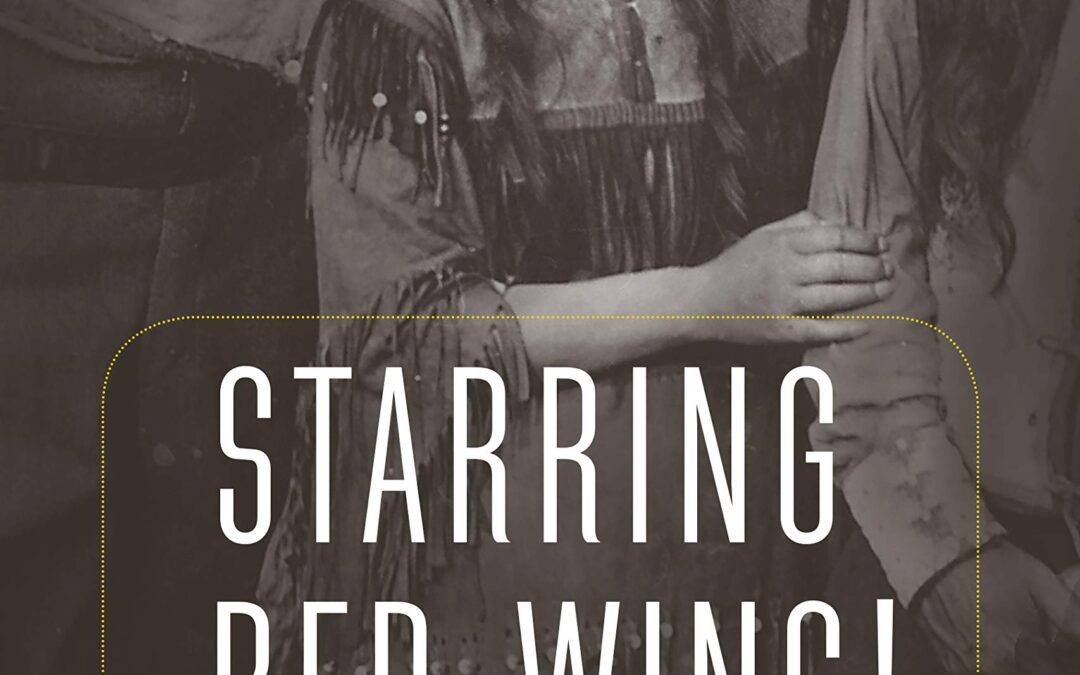

Lillian became known as Princess Red Wing, and James as Young Deer. I surmise that in the 1909 film The Mended Lute, which starred Mary Pickford (with a small role for Red Wing), the couple was instrumental in seeing that the villains were white and the honorable Indians triumphed in the end—a story trend encouraged by this team of diminutive but glamorous “influential forces.”

In 1910, Young Deer successfully directed a French-owned movie company based in New Jersey. Before his leadership, the company had been criticized for lacking realism in its Old West portrayals. This was serendipitous for James and Lillian because her acting was in Hollywood, near where James was sent to direct. Young Deer was applauded for his daredevil stunts, and he cast Red Wing as a heroine who climbed steep cliffs and leapt over canyon crevices. James went on to write scripts and eventually run the company’s West Coast studio operation. Naturally, he chose Red Wing to act in many of his 150 silent films. During Young Deer’s heyday, many directors chose Native American actors, and the indigenous characters were portrayed as stoic, honest, and of strong character.

Red Wing appeared in about a hundred, mostly short, movies, in some of which she played key roles. Her highpoint came in 1914 with her lead role in The Squaw Man, when she became the first Native American woman to star in a full-length film. She portrayed the Indian wife of an Englishman.

That same year, Young Deer left for Great Britain, both to get away from some ugly legal accusations against him and to film a thriller there. Upon his return he discovered the popularity of westerns had dipped. Simultaneously, Red Wing’s demand had lessened, and in 1915 she appeared in only two films. The problem was that she had begun to show her age and put on weight.

Concurrent with these disappointments, their marriage went downhill. Ultimately, the two divorced. By 1925 Red Wing retired from acting and hoped for solace when she married another Native American, Joe Eaglefoot. Four years later they divorced.

Lillian briefly returned to her reservation to work as a housekeeper. Shortly thereafter she created a traveling show to educate the public about Native American culture. Two years later she settled in New York and continued as a performer and educator. Her livelihood was crafting leather goods, mainly Indian costumes.

Lillian became a respected elder of New York City’s multitribal Indian community. During those latter years, she noted that only white actresses appeared in Indian parts. This continued through 1974 when, at age ninety, the former Princess Red Wing died.