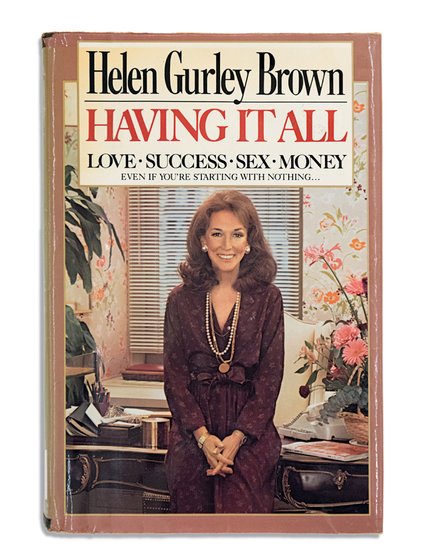

Helen Gurley Brown

1922–2012

Part I of II

Valentine’s Day is right around the corner. Some couplings are momentary, and some last a lifetime. One of my favorite “till death did us part” couples is most famous not for the husband but for the wife: Helen Gurley Brown. In 1962, after her book, Sex and the Single Girl, was published, Helen’s name became a household word for those of us born before 1950. Within three weeks it sold 2 million copies.

By then Ms. Brown was forty years old and had been married for three years. The marriage lasted till her husband, David Brown, died fifty years later. He adored Helen’s free spirit, and encouraged her to write the groundbreaking book.

The then shocking premise of Sex and the Single Girl was that sex is both an end in itself and a means to an end—the right husband. It’s noteworthy that in her book Helen bragged about sexual exploits with quite a few men before marrying David, her only husband. The success of Helen’s book and her long-lasting happy marriage to an upstanding man runs contrary to the formerly accepted thinking that a decent man wouldn’t want to marry a woman who wasn’t a virgin.

My parents, born in 1914 and 1919 respectively, were fervent believers in virginity’s value. In fact, my father had forbidden me to do the splits for fear that such a feat would break my precious hymen. His theory, however, wasn’t made clear to me until my mother relayed it years after I’d been married. At the time, both of my parents felt they’d accomplished their goal for me: to have merited a white-gown wedding ceremony.

How ironic that Sex and the Single Girl had been a blockbuster the very same year that I recited my marriage vows in order to properly experience sex. Two months before our wedding date, my fiancé drove me to the gynecologist for the mandatory pre-pill examination. The doctor seemed even older than my then forty-seven-year-old father.

Naked from the waist down, my heels in the cold metal stirrups, I couldn’t stop my legs from shaking. “Keep your knees apart,” the gruff elderly man admonished. Afterward, he refused to give me the prescription until ten days before my June ’62 wedding date.

Most baby-boomer women—born 1946 through 1964—were sexually emancipated. Those who were teens when Sex and the Single Girl became known probably bought the book for Helen’s clever tips. Many of us in the Silent Generation, born 1928 to 1945, and those born even earlier, read it to be titillated—or offended. Sex and the Single Girl was both highly applauded and highly disparaged. Two years after its publication, a film adaptation starring Natalie Wood was released. From that, Helen received $200,000 (over $1.7 million in 2021 dollars).

From age forty onward, Helen Gurley Brown had an enormous influence on the women’s sexual liberation of the 1960s. Shortly before Sex and the Single Girl was published, she had risen from pink-collar worker to well-paid advertising copywriter. In an era when a twenty-three-year-old woman was considered an old maid, Helen suggested that women not settle down with just anyone, but enjoy the search with blissful abandon however long it took. After all, she herself was thirty-seven when she married.

In 1963, a year after she released the blockbuster Sex and the Single Girl, Helen became the editor of Cosmopolitanmagazine and was widely credited with being the first to introduce frank discussions of sex into magazines for women. In the following twenty years, Cosmopolitan’s previously shrinking monthly readership rose from a less than 800,000 to nearly 3 million. Helen’s laid-back attitude and notoriety helped her keep the position as Cosmo’s US editor for thirty-four years.

Helen’s editions glamorized sex in Cosmopolitan’s articles, and the women on its covers never again looked prim and proper, but sexy. She also featured several nude-male centerfolds, including Burt Reynolds and Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Many women, including Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem, resented Helen’s concentration on attracting and pleasing men before and after having “caught” a husband. In their 1968 issue of Notes From the First Year, the feminist group New York Radical Women called her “Aunt Tom of the Month.” Kate Millett and a band of militant feminists occupied Helen’s office and demanded that she attend a consciousness-raising meeting. Helen was widely scorned for avoiding race or for dealing with it clumsily in articles such as “What It Means to Be a Negro Girl” and “The Black Man Turns Me On.”

To Be Continued