By Alice Combs | August 19, 2020 | Based on Sex, Triumph over Discrimination | 0 comments

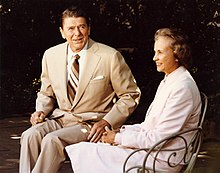

To President Trump’s chagrin, the U.S. Supreme Court often reins in his hunger for power, and for the past ten years, women have comprised at least one third of the nine justices. In 1981, sixty-one years after women won the right to vote, President Ronald Reagan nominated Sandra Day O’Connor as the first female justice of our highest court. Honored to achieve this groundbreaking position, O’Connor felt a tremendous responsibility to perform superbly so she wouldn’t also be the last woman on that bench. Her wish came true: between 1993 and 2010 three other women were appointed.

During her twenty-five-year tenure, various publications wrote of Ms. O’Connor as one of the most powerful women in the world. Three years after her retirement in 2006, President Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

This powerful woman had, however, suffered sex discrimination immediately upon graduating from the esteemed Stanford Law School. The only paid job she was offered in her field was as a legal secretary, while her young husband, also recently out of law school, had no problem finding a more prestigious job. Presumably because his income could support both of them, Ms. O’Connor was able to opt for more interesting work as an unpaid assistant to a county attorney in San Mateo, California. After she’d proven herself, San Mateo promoted her—and paid her—to be a deputy county attorney. Many promotions followed before her Supreme Court invitation, which, when she readily accepted, the Senate unanimously endorsed.

In her memoir, Out of Order, Justice O’Connor wrote, “after hearing a few thousand cases, … I long ago stopped caring what politicians and the media say about me. I was also better able to make the hard decisions that might make my powerful neighbors mad.”

Consequently, there were times when formerly friendly acquaintances refused to shake her hand. Her swing votes were unpredictable, and she indeed angered both conservatives and, more often, liberals. O’Connor joined the conservative block of Rehnquist, Scalia, Kennedy, and Thomas eighty-two times, and the liberal bloc of Stevens, Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer twenty-eight times.

Two pivotal cases in point are sequels to what Justice O’Connor considered the most important Supreme Court decision in U.S. history, Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which forbade school segregation, overturning the “separate but equal” clause decided in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In 2003, two issues tangential to integration were addressed vis-à-vis favoring “underrepresented minority groups”: 1) awarding them extra points; and 2) setting quotas for them.

In the former case, Grutter v. Bollinger, O’Connor’s swing vote pleased the liberals by allowing extra points for underrepresented minorities. She stipulated, however, that this policy should be of limited in duration, adding, “The Court expects that twenty-five years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.”

Ironically, the African American Clarence Thomas, the only Supreme Court justice who was a member of an underrepresented minority, opined that this was legislating from the bench, noting that racial preferences were as unlawful now as well as twenty-five years hence. Thomas advocated for race-neutrality, not race-fixing.

In the latter case, Gratz v. Bollinger, the O’Connor swing vote pleased the conservatives by disallowing a more rigid, point-based policy for underrepresented minority groups, which they deemed a quota system. The conservatives invalidated the claim that the proposed system was necessary to create a “critical mass” of the “underrepresented” in order to be appropriately diversified. Then the only other female Supreme Court justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, dissented, because “the stain of generations of racial oppression is still visible in our society… and the determination to hasten its removal is vital.” As a woman, I’m embarrassed that both female justices advocated ruling from the bench.

I won’t, however, insert any opinions on Bush v. Gore, which in 2000 was the most contentious case in my lifetime. When Sandra’s swing vote favored Bush, I presumed that her influence was at its apex. One could argue that it made her, temporarily, the world’s most powerful woman.